The Mightiest Indonesian Archipelago

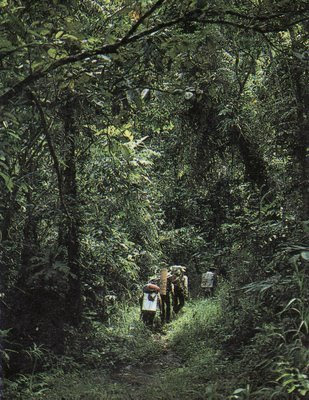

Preceding pages, aftermath of the eruption of Galunggung Volcano in West Java. Left, Mt. Mahameru makes a magnificent appearance above the clouds. Right, hiking through the Borneo rainforest in Dayak country

The Indonesian Archipelago is by far the world's largest-13,617 islands strewn across 5,120 kms (3,200 miles) of tropical seas. When superimposed on a map of North America, this means that Indonesia stretches from Oregon all the way to Bermuda. On a map of Europe, the archipelago extends from Ireland past the Caspian Sea. Of course, four-fifths of the intervening area is occupied by ocean, and many of the islands are tiny, no more than rocky outcrops populated, perhaps, by a few seabirds. But 3,000 Indonesian islands are large enough to be inhabited and New Guinea and Borneo rank as the second and third largest in the world (after Greenland). Of the other major islands, Sumatra is slightly larger than Sweden or California; Sulawesi is roughly the size of Great Britain, and Java alone is as large as England or New York State. With a total land area of 2.02 million sq kms (780,000 sq miles), Indonesia is the world's fourteenth largest political unit.

Befitting its reputation as the celebrated Spice Islands of the East, this archipelago also constitutes one of the most diverse and biologically fascinating corners of our planet. Unique geologic and climatic conditions have created spectacularly varied tropical habitats-from the exceptionally fertile rice lands of Java and Bali to the luxuriant rainforests of Sumatra, Kalimantan, Sulawesi and Maluku, to the savannah grasslands of Nusa Tenggara and the snowcapped peaks of lrian. Found here are an amazing variety of spice, aromatic had hardwood trees (clove, nutmeg, sandalwood, camphor, ebony, ironwood and teak, among others), many unusual fruits (durian, rambutan, lengkeng, salak, blimbing, nangka, manggis, jambu), the world's largest flower (the Rafflesia), the largest lizard (Komodo's monitor), many rare animal species found nowhere else (like the orangutan, the Javan rhinoceros and the Sulawesian anoa-a dwarf buffalo), thousands of varieties of butterflies and wild orchids, and many exquisite plum-age birds-- like the cockatoo and the bird of paradise.

The geological history of the region is complex. All of the islands are relatively young; the earliest dates only from the end of the Miocene, l5 million years ago-just yesterday on the geological time scale. Since that time, the whole archipelago has been the scene of violent tectonic activity, as islands were torn from jostling super continents or pushed up by colliding oceanic plates, and then enlarged in earth wrenching volcanic explosions. The process continues today-Australia is drifting slowly northward, as the immense Pacific plate presses south and west to meet it and the Asian mainland. The islands of Indonesia lie along the lines of impact, a fact that is reflected in their geography and in the great seismic instability of the region.

The islands fall into three main categories of Indonesian Archipelago. Firstly, the large islands of western Indonesia: Sumatra, Kalimantan (Borneo) and Java, together with several smaller adjacent ones (the Riau chain, Bangka, Billiton, Madura and Bali) all rest on the broad Sunda continental shelf that extends down from the Southeast-Asian mainland. The intervening Java Sea is thus very shallow, no more than 100 meters (328 feet)deep at its lowest point, and in fact these islands were often connected to each other and to the mainland during the lce Ages, when sea levels receded as much as 200 meters worldwide and the entire Sunda shelf was exposed as a huge subcontinent. Now these islands are fringed with broad plains that are continually expanding. as new alluvial deposits collect and reclaim the shallow sea.

Vast New Guinea and the tiny islands that dot the neighboring Arafura sea, are connected in similar way by the Sahul continual shelf to Australia. New Guinea was in fact torn off from Australia long ago During a rift movement of the earth's crust.

In between those continental Shelves lie Sulawesi (The Celebes), Maluku and Nusa Tenggara (the Lesser Sundas) – several rugged island arcs which rise from a deep geosynclines that drops as much as 4,500 meters (15,000 feet) below the water's surface.

Geologically all these islands were created Along fault lines where the various tectonic plates of the earth's crust collided and folded at the edges. Subsequently, volcanoes arose along several of these same fault lines.

It is possible to distinguish between two sets of symmetrical folds for each island chain in the archipelago: an older, non-volcanic outer fold and a younger, intensely volcanic inner fold. Running down the west coast of Sumatra is a non-volcanic outer range known as the Mentawai chain of islands. This continues as the southern coastal ranges of Java, Bali, Lombok and western. Sumbawa, and then splits off to form the non volcanic islands of Sumba. Roti. Sawu. Timor, and Tanimbar farther to the east. Parallel to this is an inner, highly volcanic fold that forms the central mountain spines of Sumatra, Java, Bali, Lombok, Sumbawa, and Flores, running through Alor and Wetar to the Banda islands in the east.

Befitting its reputation as the celebrated Spice Islands of the East, this archipelago also constitutes one of the most diverse and biologically fascinating corners of our planet. Unique geologic and climatic conditions have created spectacularly varied tropical habitats-from the exceptionally fertile rice lands of Java and Bali to the luxuriant rainforests of Sumatra, Kalimantan, Sulawesi and Maluku, to the savannah grasslands of Nusa Tenggara and the snowcapped peaks of lrian. Found here are an amazing variety of spice, aromatic had hardwood trees (clove, nutmeg, sandalwood, camphor, ebony, ironwood and teak, among others), many unusual fruits (durian, rambutan, lengkeng, salak, blimbing, nangka, manggis, jambu), the world's largest flower (the Rafflesia), the largest lizard (Komodo's monitor), many rare animal species found nowhere else (like the orangutan, the Javan rhinoceros and the Sulawesian anoa-a dwarf buffalo), thousands of varieties of butterflies and wild orchids, and many exquisite plum-age birds-- like the cockatoo and the bird of paradise.

The geological history of the region is complex. All of the islands are relatively young; the earliest dates only from the end of the Miocene, l5 million years ago-just yesterday on the geological time scale. Since that time, the whole archipelago has been the scene of violent tectonic activity, as islands were torn from jostling super continents or pushed up by colliding oceanic plates, and then enlarged in earth wrenching volcanic explosions. The process continues today-Australia is drifting slowly northward, as the immense Pacific plate presses south and west to meet it and the Asian mainland. The islands of Indonesia lie along the lines of impact, a fact that is reflected in their geography and in the great seismic instability of the region.

The islands fall into three main categories of Indonesian Archipelago. Firstly, the large islands of western Indonesia: Sumatra, Kalimantan (Borneo) and Java, together with several smaller adjacent ones (the Riau chain, Bangka, Billiton, Madura and Bali) all rest on the broad Sunda continental shelf that extends down from the Southeast-Asian mainland. The intervening Java Sea is thus very shallow, no more than 100 meters (328 feet)deep at its lowest point, and in fact these islands were often connected to each other and to the mainland during the lce Ages, when sea levels receded as much as 200 meters worldwide and the entire Sunda shelf was exposed as a huge subcontinent. Now these islands are fringed with broad plains that are continually expanding. as new alluvial deposits collect and reclaim the shallow sea.

Vast New Guinea and the tiny islands that dot the neighboring Arafura sea, are connected in similar way by the Sahul continual shelf to Australia. New Guinea was in fact torn off from Australia long ago During a rift movement of the earth's crust.

In between those continental Shelves lie Sulawesi (The Celebes), Maluku and Nusa Tenggara (the Lesser Sundas) – several rugged island arcs which rise from a deep geosynclines that drops as much as 4,500 meters (15,000 feet) below the water's surface.

Geologically all these islands were created Along fault lines where the various tectonic plates of the earth's crust collided and folded at the edges. Subsequently, volcanoes arose along several of these same fault lines.

It is possible to distinguish between two sets of symmetrical folds for each island chain in the archipelago: an older, non-volcanic outer fold and a younger, intensely volcanic inner fold. Running down the west coast of Sumatra is a non-volcanic outer range known as the Mentawai chain of islands. This continues as the southern coastal ranges of Java, Bali, Lombok and western. Sumbawa, and then splits off to form the non volcanic islands of Sumba. Roti. Sawu. Timor, and Tanimbar farther to the east. Parallel to this is an inner, highly volcanic fold that forms the central mountain spines of Sumatra, Java, Bali, Lombok, Sumbawa, and Flores, running through Alor and Wetar to the Banda islands in the east.

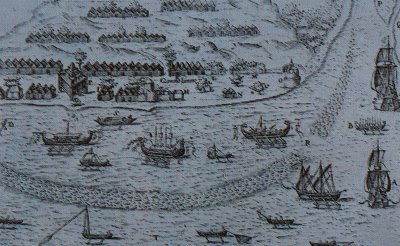

Early 16th Century Portuguese map of Southeast Asia with much ofthe Indonesian archipelago undrawn

Early 16th Century Portuguese map of Southeast Asia with much ofthe Indonesian archipelago undrawnThough structurally less well defined, a similar non-volcanic outer fold in the east forms the central ranges of New Guinea, Seram, Buru, and eastern Sulawesi, while an inner volcanic range runs up the western and northern sides of Sulawesi and Halmahera to the Philippines. Within this schema, Borneo forms. along with the Malay peninsula and the mainland, and old and stable non-volcanic core arnd Sulawesi, due to its intermediary position, is geologically the most confused a young volcanic arc (the southwestern central-northern range) welded onto an older, non-volcanic one (the eastern and south-eastern arms).

A Volcanic Legacy

The importance of volcanoes in Indonesia cannot be overstated. Not only do they dominate the landscape of many islands with majestic smoking cones, they also fundamentally alter their size and soils spewing forth millions of tons of ash and debris at irregular intervals. Much of this eventually gets washed down to form gently slopping alluvial plains. Where the ejecta is acidic. the land is infertile and practically useless for agricultural purposes.But where it is basic, as on Java and Bali and in a few scattered localities on other islands. it has Produced the most spectacularly fertile tropical soils in the world.

Of the hundreds of volcanoes, in lndonesia, over 70 remain active and hardly a year passes without a major eruption. On such a densely populated island as Java, this inevitably brings death and destruction. When Mt. Galunggung erupted in West Java in 1982, Many were killed and about 4 million were directly affected through loss of home, land and livelihood.

Yet Galunggung was only a small eruption. Tiny Mt. Krakatau off Java's west coast erupted in 1883 with a force equivalent to that of several hydrogen bombs, creating tidal waves that killed more than 35,00b people on Java. The bang of this eruption, 18 times larger than that of Mt. St. Helens, was heard as far away as Colombo and Sydney, and the great quantities of debris hurled into the atmosphere caused vivid sunsets all over the world for three years afterwards.

Even the Krakatau explosion, however, Was dwarfed by the cataclysmic 181"5 eruption of Mt. Tambora on Sumbawa-the largest in recorded history, in which 90,000 people were killed and over 80 cubic kms of ejected material blocked out the sun for many months, producing the famous "years without summer" of 1816. Geologists say that even greater explosions created Sumatra's Lake Toba and Lake Ranau eons ago.

A Volcanic Legacy

The importance of volcanoes in Indonesia cannot be overstated. Not only do they dominate the landscape of many islands with majestic smoking cones, they also fundamentally alter their size and soils spewing forth millions of tons of ash and debris at irregular intervals. Much of this eventually gets washed down to form gently slopping alluvial plains. Where the ejecta is acidic. the land is infertile and practically useless for agricultural purposes.But where it is basic, as on Java and Bali and in a few scattered localities on other islands. it has Produced the most spectacularly fertile tropical soils in the world.

Of the hundreds of volcanoes, in lndonesia, over 70 remain active and hardly a year passes without a major eruption. On such a densely populated island as Java, this inevitably brings death and destruction. When Mt. Galunggung erupted in West Java in 1982, Many were killed and about 4 million were directly affected through loss of home, land and livelihood.

Yet Galunggung was only a small eruption. Tiny Mt. Krakatau off Java's west coast erupted in 1883 with a force equivalent to that of several hydrogen bombs, creating tidal waves that killed more than 35,00b people on Java. The bang of this eruption, 18 times larger than that of Mt. St. Helens, was heard as far away as Colombo and Sydney, and the great quantities of debris hurled into the atmosphere caused vivid sunsets all over the world for three years afterwards.

Even the Krakatau explosion, however, Was dwarfed by the cataclysmic 181"5 eruption of Mt. Tambora on Sumbawa-the largest in recorded history, in which 90,000 people were killed and over 80 cubic kms of ejected material blocked out the sun for many months, producing the famous "years without summer" of 1816. Geologists say that even greater explosions created Sumatra's Lake Toba and Lake Ranau eons ago.

Climate

Early Dutch painting depicts a Sumatran volcano

Early Dutch painting depicts a Sumatran volcanoAll of the islands in the archipelago lie within the tropical zone, and the surrounding seas exert everywhere a homogenizing effect on temperatures and humidity, so that local variables like topography, altitude and rainfall produce more variation in climate than do latitude or season. Mean temperatures at sea level are uniform, varying by only a few, degrees throughout the region-, and throughout the year (25-28 C/78-82 FF).

In the mountains, however, the temperature decreases about one degree C (two degrees F) for every 200 meters (656 feet) of-altitude, which makes for a cool, pleasant climate in upland towns like Bandung (in West Java: altitude 900 meters [2,950- it]) and Bukit Tinggi (in West Sumatra: altitude 1,000 meters [3.280 ft]).

Much of the Indonesian Archipelago also lies within the equatorial ever wet zone, where no month passes without several inches of rainfall. Most islands receive considerably more than this during the northeast monsoon, which blows down over the South China Sea picking up moisture, then veers to the northwest across the equator, unleashing drenching precipitation wherever it touches land from November through April. Moreover, the tropical sun and the oceans combine to produce continuously high humidity everywhere, and due to local wind patterns, a few places, like Bogor in West Java, receive rain almost daily-as much as 400 cm (200 inches) of it annually!

The Southeast Monsoon nevertheless tends to counteract this generally high humidity by blowing hot, dry air up from over the Australian landmass between May and October. Though much depends on local topography, on most islands this produces a dry season of markedly reduced precipitation, and as one moves south and eastward in the Indonesian Archipelago, the influence of this dessicating Southeast Monsoon increases dramatically. Thus, for example, Sumba and Timor in the Nusa Tenggara chain have an extremely long dry season, with occasional two years droughts. Similarly, the southern Bukit peninsula in Bali is much drier than the rest of the island. as are parts of Java east and south of Surakarta.

In the mountains, however, the temperature decreases about one degree C (two degrees F) for every 200 meters (656 feet) of-altitude, which makes for a cool, pleasant climate in upland towns like Bandung (in West Java: altitude 900 meters [2,950- it]) and Bukit Tinggi (in West Sumatra: altitude 1,000 meters [3.280 ft]).

Much of the Indonesian Archipelago also lies within the equatorial ever wet zone, where no month passes without several inches of rainfall. Most islands receive considerably more than this during the northeast monsoon, which blows down over the South China Sea picking up moisture, then veers to the northwest across the equator, unleashing drenching precipitation wherever it touches land from November through April. Moreover, the tropical sun and the oceans combine to produce continuously high humidity everywhere, and due to local wind patterns, a few places, like Bogor in West Java, receive rain almost daily-as much as 400 cm (200 inches) of it annually!

The Southeast Monsoon nevertheless tends to counteract this generally high humidity by blowing hot, dry air up from over the Australian landmass between May and October. Though much depends on local topography, on most islands this produces a dry season of markedly reduced precipitation, and as one moves south and eastward in the Indonesian Archipelago, the influence of this dessicating Southeast Monsoon increases dramatically. Thus, for example, Sumba and Timor in the Nusa Tenggara chain have an extremely long dry season, with occasional two years droughts. Similarly, the southern Bukit peninsula in Bali is much drier than the rest of the island. as are parts of Java east and south of Surakarta.

Arboreal Canopies

Mangrovesa long the Cihandeuleum River at Ujung Kulon

Mangrovesa long the Cihandeuleum River at Ujung Kulonin West Java

The vegetation found in different parts of the Indonesian Archipelago varies greatly according to rainfall, soil and altitude. On the wetter equatorial islands. the Luxuriance of the rain forests is simply amazing The main canopy of interlocking tree crowns mar be -10 meters (130 ft) from the ground. with individual trees rising as high as 7 meters (230 ft). Beneath this grows a tangle of palms, lianas, Epiphytic ferns, rattans and bamboos, covered by innumerable lichens, mosses and lower plants.

One would imagine that to support such growth the soils would have to be very rich, but this is generally not so. The rain forests of Sumatra, Kalimantan, Sulawesi and Irian typically thrive on very poor and thin soils, that have been heavily leached of minerals by the incessant rains. Cleared of their forest cover by shifting agriculturalists, they support only two or three Meagre crops before being exhausted, eroded or choked with weeds.

How does the rain forest flourish in such circumstances? The answer lies in the nature of its ecosystem, which has brilliantly adapted over millions of years to just such conditions. Essentially, the system holds most of its minerals and nutrients in the form of living tissues. As these die and fall to the ground, they are immediately decomposed and absorbed back up into the system once again. In effect, then, the Rainforest is a self-fertilizing system largely independent of the soil.

On each level, various plants play unique roles in the ecosystem. The upper tree canopy absorbs sunlight and photosyn the-size sit , while maintaining low temperatures and high humidity below. Growth is very slow on the shady lower levels. Lianas wind up from the ground; rattan canes use hooked barbs to grapple and climb; epiphytes simply settle on the branches of big trees.

All plants in the system face shortages of minerals and water, and have therefore developed water storage tubers and other strategies, such as providing shelter and special fluids for ants who in turn deposit their nutrient-rich faces for the plant to use. Some plants resort to piracy, living as parasites-like the garish Rafflesia flower found only in south-central Sumatra, which has no leaves and lives on the ground trailing Tetrastigma vine. Its cabbage-like buds swell and eventually burst open in enermous blooms, five reddish-brown petals splashed with white that can measure one metre across and sometimes weigh nine kgs (20 lbs).

One would imagine that to support such growth the soils would have to be very rich, but this is generally not so. The rain forests of Sumatra, Kalimantan, Sulawesi and Irian typically thrive on very poor and thin soils, that have been heavily leached of minerals by the incessant rains. Cleared of their forest cover by shifting agriculturalists, they support only two or three Meagre crops before being exhausted, eroded or choked with weeds.

How does the rain forest flourish in such circumstances? The answer lies in the nature of its ecosystem, which has brilliantly adapted over millions of years to just such conditions. Essentially, the system holds most of its minerals and nutrients in the form of living tissues. As these die and fall to the ground, they are immediately decomposed and absorbed back up into the system once again. In effect, then, the Rainforest is a self-fertilizing system largely independent of the soil.

On each level, various plants play unique roles in the ecosystem. The upper tree canopy absorbs sunlight and photosyn the-size sit , while maintaining low temperatures and high humidity below. Growth is very slow on the shady lower levels. Lianas wind up from the ground; rattan canes use hooked barbs to grapple and climb; epiphytes simply settle on the branches of big trees.

All plants in the system face shortages of minerals and water, and have therefore developed water storage tubers and other strategies, such as providing shelter and special fluids for ants who in turn deposit their nutrient-rich faces for the plant to use. Some plants resort to piracy, living as parasites-like the garish Rafflesia flower found only in south-central Sumatra, which has no leaves and lives on the ground trailing Tetrastigma vine. Its cabbage-like buds swell and eventually burst open in enermous blooms, five reddish-brown petals splashed with white that can measure one metre across and sometimes weigh nine kgs (20 lbs).

Montane forest at Cibodas in West Java

Montane forest at Cibodas in West JavaCarnivorous pitcher plants lure unsuspecting insects into liquid-filled cups, where they are dissolved to provide essential nutrients. And the strangler fig settles on a lofty branch, putting down aerial roots that eventually strangle the host tree itself.

Lowland-rain forests display the greatest diversity. Stands of a single tree are rare, rather the lowland forest is composed of a fantastic mosaic of different species, so that in Borneo alone. for example, 3,000 different tree species are known. On this and other islands, many economically valuable hardwood, aromatic and spice trees flourish-including teak, ebony, sandalwood, camphor, clove and nutmeg trees, as well as exotic fruit-bearing species: durian, rambutan, jackfruit, salak, jambu, tamarind, breadfruit and hundreds of varieties of banana and fruit-bearing palms. In New Guinea more than 2,500 species of wild orchids are found in the rainforest, including the world's largest-the tiger orchid (Grammatophyllum Speciosum) with its three meter-long spray of yellow-orange blooms.

Lowland-rain forests display the greatest diversity. Stands of a single tree are rare, rather the lowland forest is composed of a fantastic mosaic of different species, so that in Borneo alone. for example, 3,000 different tree species are known. On this and other islands, many economically valuable hardwood, aromatic and spice trees flourish-including teak, ebony, sandalwood, camphor, clove and nutmeg trees, as well as exotic fruit-bearing species: durian, rambutan, jackfruit, salak, jambu, tamarind, breadfruit and hundreds of varieties of banana and fruit-bearing palms. In New Guinea more than 2,500 species of wild orchids are found in the rainforest, including the world's largest-the tiger orchid (Grammatophyllum Speciosum) with its three meter-long spray of yellow-orange blooms.

Alpine Forests and Mangrove Swamps

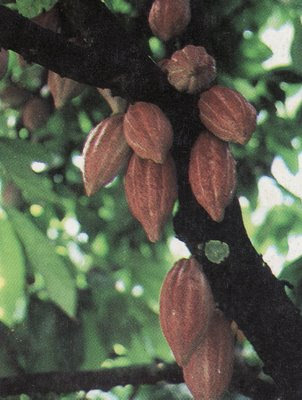

Fruit of the cacao tree

Fruit of the cacao treeAt high altitudes, temperatures drop and cloud cover increases, resulting in slower growth, fewer species and less complex structure. Rain forest give way to more specialized montane forests, dominated by chestnuts, laurels and oaks. Higher up, one finds rhododendrons and stunted moss forests-dwarf trees draped in lichens. Higher still, there are alpine meadows with Giant edelweiss and other plants more reminiscent of Switzerland than Indonesia. This unexpected habitat can be seen a t Mt. Gede National Park, only 100k ms ( 62m iles) south of hot, humid Jakarta. Indonesia's highest peaks, the Lorentz mountains of Irian Jaya, rise to over 5,000 meters (16,000 feet), and are clad in permanent now fields and glaciers, the only rice fields in the eastern tropics.

Other specialized forests grow on ultra basic rocks, on limestone Karsts, in young volcanic areas and in poorly drained swamps where lack of aeration leads to the build-up of acid peat. In the vast tidal zones of eastern Sumatra, Kalimantan and southern Irian, specialized mangrove trees with looping roots and air-breathing nodules flourish. These trap silt washed down by rivers and creep slowly forward behind a wall of growing coral, forming new land. Mangrove swamps are inhabited by fiddler crabs, fish that skip out of the water, dancing fireflies and the amazing proboscis monkey unique to Borneo.

Moving east from central Java across Bali and Nusa Tenggara, the climate becomes drier and lowland jungles are replaced by deciduous monsoon forests and open savannah grasslands. Depending on how dry the climate is, these forests are partly or wholly deciduous, with fewer species and many broad-leaf trees like teak, which shed their leaves during the dry season. This renders them highly vulnerable to forest fires, and indeed most of the natural forests on Sumbawa, Komodo, Flores and Timor have been either cut or burned off in recent centuries by man. The exposed land has then been devoured by voracious alang-alang (elephant grasses), so that today there are only useless grasslands and scrub where once there were valuable hardwood forests.

Other specialized forests grow on ultra basic rocks, on limestone Karsts, in young volcanic areas and in poorly drained swamps where lack of aeration leads to the build-up of acid peat. In the vast tidal zones of eastern Sumatra, Kalimantan and southern Irian, specialized mangrove trees with looping roots and air-breathing nodules flourish. These trap silt washed down by rivers and creep slowly forward behind a wall of growing coral, forming new land. Mangrove swamps are inhabited by fiddler crabs, fish that skip out of the water, dancing fireflies and the amazing proboscis monkey unique to Borneo.

Moving east from central Java across Bali and Nusa Tenggara, the climate becomes drier and lowland jungles are replaced by deciduous monsoon forests and open savannah grasslands. Depending on how dry the climate is, these forests are partly or wholly deciduous, with fewer species and many broad-leaf trees like teak, which shed their leaves during the dry season. This renders them highly vulnerable to forest fires, and indeed most of the natural forests on Sumbawa, Komodo, Flores and Timor have been either cut or burned off in recent centuries by man. The exposed land has then been devoured by voracious alang-alang (elephant grasses), so that today there are only useless grasslands and scrub where once there were valuable hardwood forests.

A wet-rice paddy in Sumba is "ploughed" by water buffal

A wet-rice paddy in Sumba is "ploughed" by water buffalMan's presence in the archipelago has not always had an adverse impact on the environment. Indeed, since prehistoric times, man has created exceptionally productive agricultural environments on islands like Java and Bali. This was accomplished through the introduction of irrigated wet rice cultivation to areas that already possessed soil and climatic conditions ideal for agriculture.

Not only are Java and Bali among the few islands where volcanic ejecta is basic and not acidic, so that frequent volcanic eruptions have in fact continually improved the soils by adding mineral-rich nutrients, but they are also areas which achieve something of a golden mean in climate, between the incessant rainfall of the equatorial islands and the extended droughts oT Nusa Tenggara. Java and Bali receive plentiful rainfall and sunshine during alternating dry and wet seasons, each of which lasts half of the year.

It remained, then, for man to harness these natural blessings to his advantage, through the construction of elaborate irrigation networks and labor-intensive wet-rice paddies. The results have been astounding-rice yields under traditional conditions (i.e. before the use of chemical fertilizers and miracle rice strains) that are by far the highest in the world. Such extraordinary fecundity, responsible in great measure for the numerous cultural achievements of the Javanese and the Balinese, has now resulted in runaway population growth. Java today supports 100 million people, two-thirds of Indonesia's population, on only seven per cent of the nation's total land area. This represents an average of over 750 persons per sq km (2.000 per sq mile)-more than twice that of densely populated industrial nations like Japan and Holland. And in many areas of Java, average rural population densities actually soar to an incredible 2,000 persons per sq km (5,000 per sq mile)!

The situation on other islands stands in marked contrast to this. The remaining 50 million Indonesians live spread over more than 90 per cent of the Indonesian Archipelago, with an average population density of only 35 per sq km (90 per sq mile). On some islands, like Kalimantan and Irian,Jaya, this figure drops to around 10 per sq km.

Not only are Java and Bali among the few islands where volcanic ejecta is basic and not acidic, so that frequent volcanic eruptions have in fact continually improved the soils by adding mineral-rich nutrients, but they are also areas which achieve something of a golden mean in climate, between the incessant rainfall of the equatorial islands and the extended droughts oT Nusa Tenggara. Java and Bali receive plentiful rainfall and sunshine during alternating dry and wet seasons, each of which lasts half of the year.

It remained, then, for man to harness these natural blessings to his advantage, through the construction of elaborate irrigation networks and labor-intensive wet-rice paddies. The results have been astounding-rice yields under traditional conditions (i.e. before the use of chemical fertilizers and miracle rice strains) that are by far the highest in the world. Such extraordinary fecundity, responsible in great measure for the numerous cultural achievements of the Javanese and the Balinese, has now resulted in runaway population growth. Java today supports 100 million people, two-thirds of Indonesia's population, on only seven per cent of the nation's total land area. This represents an average of over 750 persons per sq km (2.000 per sq mile)-more than twice that of densely populated industrial nations like Japan and Holland. And in many areas of Java, average rural population densities actually soar to an incredible 2,000 persons per sq km (5,000 per sq mile)!

The situation on other islands stands in marked contrast to this. The remaining 50 million Indonesians live spread over more than 90 per cent of the Indonesian Archipelago, with an average population density of only 35 per sq km (90 per sq mile). On some islands, like Kalimantan and Irian,Jaya, this figure drops to around 10 per sq km.

> Climbing a lontar palm for tuak

Climbing a lontar palm for tuak

Climbing a lontar palm for tuak

Climbing a lontar palm for tuakPartly in view of this dramatic population imbalance and partly because of the historical importance of Java as a political center of gravity within the Indonesian Archipelago, many observers tend to distinguish between an Inner Indonesia (i.e. Java and Bali, including Madura and West Lombok) and an Outer Indonesia (all other islands).

Whereas Inner Indonesia has been characterized for centuries by high population densities and labour-intensive irrigated agriculture, Outer Indonesia is the home, traditionally, of dense rain forests, thinly-spread shifting agricultural communities and riverie trading networks. Now, the Outer Islands are also the source of almost all valuable exports: rubber and palm oil (from Sumatran estates), petroleum, copper, tin and bauxite (from Sumatra, Bangka, Billiton and Irian Jaya) and timber (from Kalimantan).

In a sense, the serious ecological problems of over-populated Inner Indonesia are now being exported to the Outer Islands. Java has already suffered for some time from problems of erosion, soil exhaustion and pollution. Now, as the nation's export resources are increasingly being called upon to support a burgeoning population, there are the beginnings of massive deforestation, leading to erosion and the replacement of rainforest by useless grassland.

Whereas Inner Indonesia has been characterized for centuries by high population densities and labour-intensive irrigated agriculture, Outer Indonesia is the home, traditionally, of dense rain forests, thinly-spread shifting agricultural communities and riverie trading networks. Now, the Outer Islands are also the source of almost all valuable exports: rubber and palm oil (from Sumatran estates), petroleum, copper, tin and bauxite (from Sumatra, Bangka, Billiton and Irian Jaya) and timber (from Kalimantan).

In a sense, the serious ecological problems of over-populated Inner Indonesia are now being exported to the Outer Islands. Java has already suffered for some time from problems of erosion, soil exhaustion and pollution. Now, as the nation's export resources are increasingly being called upon to support a burgeoning population, there are the beginnings of massive deforestation, leading to erosion and the replacement of rainforest by useless grassland.

A tea plantation in the cool uplands of Java

A tea plantation in the cool uplands of JavaThese problems have been recognized by the Indonesian government. Realizing, for example, that if indiscriminate clear-felling in Kalimantan timber concessions continues at its present rate, there will be no lowland forest left by the end of the century, they are taking steps to encourage selective cutting and reforestation. Moreover, six per cent of the nation's land has been set aside as nature reserves and national parks. These are not just for the protection of a few wild animals-they safeguard a genetic treasure trove containing many species that may be valuable to man, as well as providing watershed protection and recreational facilities.

(Jakarta's Gunung Sahara Street in the early fifties, a time of national reconstruction)

(Jakarta's Gunung Sahara Street in the early fifties, a time of national reconstruction) Sukarno (center) with his first cabinet, of which Hatta (right of Sukarno) was vice-president

Sukarno (center) with his first cabinet, of which Hatta (right of Sukarno) was vice-president ( Nehru (left) standing with Sukarno(right) During a state visit of 1957)

( Nehru (left) standing with Sukarno(right) During a state visit of 1957) (Right, Soekarno reads a statement to the press handing over power,

(Right, Soekarno reads a statement to the press handing over power, (In Jakarta, the monument commemorating

(In Jakarta, the monument commemorating (Early oil exploration in Sumatra-where Indonesia's vital

(Early oil exploration in Sumatra-where Indonesia's vital (As the world'sfifth largest OPEC producer,the nation's economy is heavily dependent on oil)

(As the world'sfifth largest OPEC producer,the nation's economy is heavily dependent on oil) (Indonesia is also the world's exporter of natural gas)

(Indonesia is also the world's exporter of natural gas)

(Opposition to the Dutch found a voice in groups such as these medical students)

(Opposition to the Dutch found a voice in groups such as these medical students) (The movement for Independence Day Of Indonesia spawned marches and gatherings.

(The movement for Independence Day Of Indonesia spawned marches and gatherings. (Bung Tomo, an Indonesian hero from Surabaya)

(Bung Tomo, an Indonesian hero from Surabaya)

(Early Dutch expedition to Java)

(Early Dutch expedition to Java) (Van Lisnschoten - author of the first "guide book" to the Indies)

(Van Lisnschoten - author of the first "guide book" to the Indies) (Jan Pieterszoon Coen, architect of Dutch empire in the East)

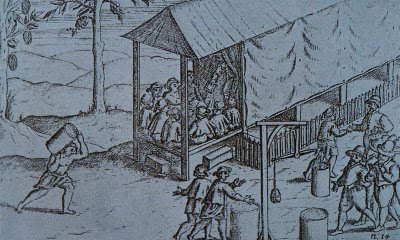

(Jan Pieterszoon Coen, architect of Dutch empire in the East) (Natives bring nutmegs for sale to a Dutch trading post at Banda Neira)

(Natives bring nutmegs for sale to a Dutch trading post at Banda Neira) (On the site of Jayakarta, the new town of Batavia had many of the features

(On the site of Jayakarta, the new town of Batavia had many of the features

(The Dutch Army poses after a victory over Acehnese forces)

(The Dutch Army poses after a victory over Acehnese forces) (Susuhunan Pakubuwono X of Surakarta poses with a Dutch administrator.

(Susuhunan Pakubuwono X of Surakarta poses with a Dutch administrator.

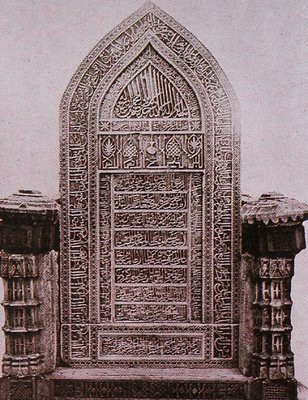

(Print of the historic mosque at Banten -

(Print of the historic mosque at Banten - Muslim traders had a crucial role in expansion of Islam)

Muslim traders had a crucial role in expansion of Islam) (Worshippers in a mosque)

(Worshippers in a mosque)