Welcome-to-the-Greenhouse, originally uploaded by mix's.

This post is an English version of my article published in the Indonesian newspaper of Kompas on Tuesday, December 15, 2009.

The attention to climate change and global warming is now on the United Nations Climate Change Conference in Copenhagen, Denmark on December 7-18, 2009. This conference is expected to reach a new agreement on decreasing global emissions of greenhouse gases after the ending of the Kyoto Protocol in 2012.

As one of the tropical countries with large forest areas, Indonesia is expected to play an important role in absorbing the emissions of carbon dioxide that cause the increase of greenhouse gases in the atmosphere. Transtoto Handadhari (Kompas, December 7, 2009) reported that Indonesian forests have the carbon dioxide absorption as many as 25,733 billion tons excluding peat forests and dry lands. The government of Indonesia set a target of reducing the carbon emissions by 26 percent in 2020 through many ways including the expansion of new forests as much as a half hectare per year, the expansion of community forests about 4 million hectares, and the decrease of hot spots about 20 percent.

The decrease of carbon dioxide emissions for addressing the global warming is not only the responsility of those who work in forests, but also that of all citizens. Urban residents play also an important role in decreasing the carbon dioxide emissions. Human activities that use fossil fuel are a big contributor in the global warming. Increasing the efficiency of electricity uses such as lighting, cooling or the uses of electronic tools and recycling are some ways that can be offered to address the global warming.

Copenhagen UN Climate Change Conference, originally uploaded by United Nations Photo.

Urban Green Areas

Urban development can be also aimed at addressing the global warming. Urban green areas are often sacrificed in urban developments in order to keep up with the fast-growth of urban population. Jakarta, for instance, in 1965 had green areas as much as 30% of the total Jakarta areas, and the proportion of green areas has been decreasing to 9.3% in 2009. The decrease of green areas also occurs in most Indonesian cities. Green areas are an important component of urban development, not only to create a city more beautiful and greener, but also to absorb carbon dioxide from human activities particularly transportation.

Green areas can also play a role of mitigating the impact of climate change such as floods and the rise of sea level. Green areas can be water catchment areas for preventing floods. In metropolitan areas, such as Jakarta, the area vulnerability to global warming will be even higher due to the land subsidence that is caused by extensive underground water exploitation.

The expansion of green areas should be one of the urban development priorities in in Indonesia. The ideal of green areas in urban areas is 30% of the total urban area as stipulated in the Spatial Planning Law 26/2007. This number is not easy, but is not impossible to achieve either. Lately, the Jakarta administration closed 27 gas stations located in green areas and converted them into green areas. Such a decision demonstrates a strong commitment from the Jakarta administration to expand green areas and can be followed by other cities in Indonesia or even in the world.

Mass Transit and Urban Sprawl

Urban development in metropolitan areas such as Jakarta needs to develop mass transit such as subway and monorail. The current public transportations such as busway and other public transportations need to expand the services and integrate with the needs and affordability of residents. Converting private vehicles to mass transits or other public transportation will reduce the use of fossil fuel. The decrease of fuel usage per capita in transportation will significantly reduce the carbon emission.

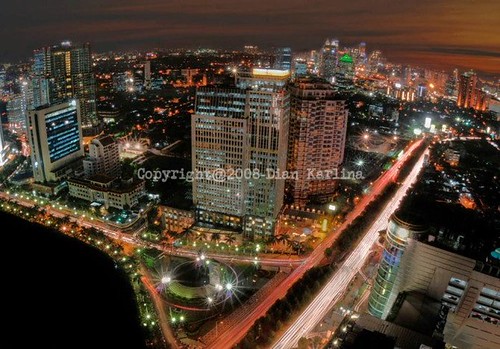

Planet Jakarta, originally uploaded by diankarl **will visit you soon**.