Indonesia Since Independence Day, Euphoria swept through the cities and towns of Indonesia following the withdrawal of Dutch forces and the secular of Indonesian sovereignty. Mass rallies and processions were held: flag-waving crowds thronged the streets shouting the magical words: " Merdeka, Merdeka!" (Freedom, freedom!). Independence had come at last, and though many obstacles remained Indonesian felt that nothing was impossible now that they held their destiny in their own hands.

Meanwhile. in Jakarta. the slow and arduous process of constructing a peacetime Government had begun. And while the uni-flying power of th6 revolution had done much to forge a coherent state, the fact of Indonesia's remarkable ethnic, religious and ideological diversity remained. Moreover, massive economic and social problems faced the new nation-a legacy of colonialism and war. Factories and plantations were shut down, capital and skilled personnel were scarce, rice production was insufficient to meet demand, the Indonesian people were overwhelmingly poor and illiterate, and the population was growing at an unprecedented.

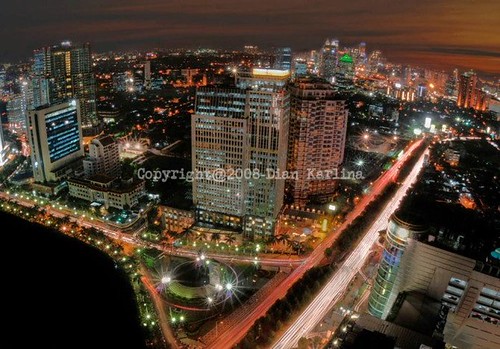

(Jakarta's Gunung Sahara Street in the early fifties, a time of national reconstruction)

The inability of any single political group of Indonesia since independence day to effectively dominate it to others clearly called for a system of government in which a variety of interests could be represented. Largely due to the high profile of Dutch-educated intellectuals among the nationalists, a western-style parliamentary system of government was adopted.

From the beginning of Indonesia since independence day, however, the existence of more than 30 rival parties paralyzed the system. A string of weak coalition cabinets rose and fell at the rate of almost one a year, and attempts at cooperation were increasingly stymied not only by a growing ideological polarization, but also by religous and regional loyalties. Parties became more and more preoccupied with ensuring their own survival and less and less attentive toward the nation's pressing economic and social needs,frustrating those who wished to see the revolution produce more tangible results. Most impatient of.all were Sukarno, whose powers as President had been limited b-ythe provisional constitution of 1950, and the army leadership, who felt that their key role during the revolution entitled them to a greater political say.

A series of-uprisings by disaffected groups in Sumatra, North Sulawesi and West Java ever-popular Sukarno declared martial law and give a free hand to crush the rebels. By 1959. with the rebellions under control, Sukarno resurrected the '-revolutionary" constitution of 1945 and declared the beginning of Guided Democracy.

Guided Democracy

1959 - 1965Indonesia since independence day, under the new political system, power as focused in the hands of the President and the army leadership, at the expense of political parties, whom Sukarno now resarded as counter-revolutionary. Militant nationalism became Sukarno's new recipe for national integration, and the blame for all sorts of economic and political problems was placed squarely at the feet of foreign imperialism and colonialism. In the international arena, Sukarno had, in 1955, made a significant impact by convening the Asia Africa Conference in Bandung. Attended by leaders such as Chou En-lai, Nehru and Nassar, the conference led to the formation of a non-aligned movement and placed Indonesia in the forefront among emergent Third World nations.

Sukarno (center) with his first cabinet, of which Hatta (right of Sukarno) was vice-president

In the early 1960s Soekarno's anti-colonial sentiments took a more militant turn. A long and successful campaign to wrest control of western New Guinea from the Dutch was followed closely by military confrontation with newly independent Malaysia, in 1963. Sukarno's audacity and growing contempt for the United States ("To hell with your aid!" he told the Americans) earned him the reputation of infant terrible among Asian leaders.

Soekarno's nationalistic 6lan was in some ways just what Indonesia needed. Many Indonesians saw in him a kind of father figure-a natural leader who offered a vision of a strong and independent Indonesia not seen since the 14th Century, during the reign of the powerful empire,of Majapahit.

Yet Soekarno's reliance on his charisma, and his lack of attention to day-to-day administration created a vacuum in which the government and the nation floundered. While Soekarno attempted to offset the growing influence of the military by identifying himself more closely with the most active of the civilian parties, the communist PKI, the nation's economy ground to a halt. Foreign investment fled, deficits left the government bankrupt and inflation skyrocketed to an annual rate of 680 per cent. By 1965, the year that Sukarno christened, "The Year of Living Dangerously," social, cultural and political ferment was intense.

The 1965 CoupThe political tinderbox was ignited in the early hours of Oct 1, 1965 when with the apparent encouragement of the PKI. a group of radical young army officers kidnaped and brutally .Executed six leading generals, claiming that they were plotting against the President. Failing to gain Soekarno's backing. however. the rebel officers soon lost the initiative to General Soeharto, then head of the elite Army Strategic Reserve. In the space of a few hours.Soeharto moved to assume command of the army and to crush the attempted coup.

( Nehru (left) standing with Sukarno(right) During a state visit of 1957)

The nation was shocked by news of the generals' execution.and. although the exact extent to which PKI leaders were involved is still not clear, the communists were charged with attempting to overthrow the government. A state of anarchy ensued, in which moderate, Muslim and army elements sought to settle the score. Thousands upon thousands were killed as long-simmering frustrations erupted into mob violence first in northern Sumatra, then later in Java,Bali and Lombok. The bloodletting continued for months, and the period 1965-66 is remembered today as the darkest in the Republic's history.

Meanwhile.in Jakarta. a political struggle broke out between the army, supported by students, intellectuals. Muslims and other middle-class groups on the one hand, and Sukarno, with his considerable populist/nationalist following on the other. Finally on March 11th, 1966, Sukarno was persuaded to sign a document bestowing wide powers on General Suharto.

Although Suharto was not formally installed as Indonesia's second president until 1968, immediate reforms were carried out under his direction. Martial law was declared and order was restored. 'the communist party, Marxist-Leninist teachings were outlawed. The civil administration was radically restructured and restaffed by military personnel. A major realignment in foreign policy restored relations with the United States and the West, while severing ties with China and the Soviet Union.

Economic 'New Order"Indonesia since independence day building its political legitimacy upon promises to revive the moribund Indonesian economy, the new Suharto administration wasted no time in addressing the fundamental problems of inflation and stagnation. American-trained economists were called upon to over see the rapid reintegration of Indonesia into the world economy. and in a short space of time, foreign investment laws were liberalized, monetary controls were imposed, and western aid was sought and received to replenish the nation's exhausted foreign exchange reserves. These measures formed the cornerstones of Suharto's economic "new order." and served to dramatically curb inflation and to set the nation on a course of rapid economic growth by the early l970s.

(Right, Soekarno reads a statement to the press handing over power,

while his success or Suharto looks on)

Indonesian first five-year plan. Repelita I was design to encourage growth by attracting foreign investment. Most of the targets of the plan were achieved-a first wave of investors moved in to take advantage of Indonesia's vast natural reserves of copper,tin, timber and oil, setting up facilities to extract these raw materials in Sumatra, Sulawesi, Kalimantan and Irian Jaya. As the political stability of the region seemed more assured a second wave of investors, largely Japanese and local Chinese, set up a wide variety of urban-based manufacturing industries. By 1915, textile manufacturing alone accounted for US$708 million worth of investments, and the economy was rocketing.

By far the greatest benefits, however, came from oil. The story began in northern Sumatra in 1883 when a Dutch planter took shelter from a storm in a native shed and noticed a wet torch burning brightly. Inquiring about this, he was led to a near by spring where a black viscous substance lay thick across the water. The discovery soon led to the formation of Royal Dutch shell Company, and eventually to the establishment of Indonesia as the world's fifth largest OPEC producer.

From a total of US$323million in i966, oil exports rose to US$5.2 billion in 1974, largely due to the steep OPEC price hikes of the early 1970s. Now oil has come to account for roughly 60 per cent of the state's total revenues, and the flood of petrodollars has been used to fund not only a number of capital works programs but also a significant upgrading of the nation's huge civil service.The most impressive advances have been in education. particularly at the primary level. Between 1912 and [97t1. no less than 26,677 primary schools were built, bringing the percentage of children enrolled from 69 to 84. Primary school teachers now account for roughly I third of the nation's 2.3 million government employees.

Indonesia's civil service though is not without its problems. Despite 106 per cent across-the-board wage hikes in the early 1970s,pay levels remain low. In 1983,over 70 per cent of civil servants were receiving less than US$20 per week. Inefficiency and corruption are the result, compounding a serious lack of expertise and training. Only 26 per cent of all government employees (including teachers)have more than a junior high school education.

A different sort of problem arose within the government body responsible for the oil bonanza, the State Oil and Natural Gas Corporation, Pertamina. In the early 1970s, under the direction of Colonel Ibnu Sutowo. Pertamina poured huge sums of money into projects intended to reduce Indonesia's dependence on foreign technology and imports. These included a floating fertilizer plant to be anchored over offshore gas fields, the massive Krakatau steel mill in West Java, a three-million-ton tanker fleet, petrochemical and refining plants, as well as several non-industrial projects such as a first-class hospital, a sports stadium, a chain of hotels, an airline and a golf course.

(In Jakarta, the monument commemorating

the "liberation" of lrian Jaya)

Ibnu Sutowo's flamboyant spending came to an abrupt halt in 1975, when Pertamina announced that it was defaulting on one of its foreign bank loans. Sutowo,it turned out, had recklessly borrowed money that he had no chance of repaying, clocking up over $10 billion in foreign debts in the process!In the end, the Indonesian government was saddled with one of the largest peace time losses any country has ever suffered, and many industrial projects had to be scrapped or rescheduled.

Peace and ProgressDespite these and other problems, the 1970s and early 1980s have been characterized by relative political stability. The tenor of the Suharto regime and its supporters is well caught by the slogan, "Development yes,politics n-o!"Opposition political parties have been restricted and closely supervised, managing to poll only 40 per cent in the 1971 election and even less in 1977 and 1982. The big winner. meanwhile, has been the government's political "functional" group, Golkar, consisting of representatives chosen from various professional, religious, ethnic and military constituencies.

Yet politics refused to go away entirely. A proposed secular marriage law brought an angry response from Indonesia's Muslim majority in 1973 and had to be dropped. And pressure has mounted for the government to provide for a greater distribution of the wealth and benefits of economic growth, to curb the level of foreign debt, to contain inflation and to eradicate corruption. Frustration, particularly over economic matters, has erupted in the past, notably on the occasion of Japanese Prime Minister Tanaka's visit to Jakarta in I974, when the capital was rocked by two days of violent student demonstrations.

Among the influential middle class, however, opposition has been muted by the very prosperity the "New Order" has helped to generate. Most Indonesians consider themselves better off today than ever before-there are far more cassette players, motorbikes, cars, telephones, televisions and other consumer goods around than there have ever been.

Striking advances have also been made in the vital areas of population control and agriculture. In 1980, Indonesia's population was counted at 147 million. Java and Bali are the most seriously over crowded islands,representing only seven per cent of Indonesia's total land area, while housing two thirds of her people-equivalent to the entire population of the United States occupying the state of California.

The government first attempted to ease the pressure with transmigration-the resettlement of Javanese and Balinese villagers to the sparsely populated islands of Sumatra, Kalimantan and Sulawesi. Transmigration has proved slow and costly, though, and since 1970 has been complemented by an intensive family planning campaign, that has managed to reduce the birth rate from over two per cent to around 1.8 per cent per annual.

Directly linked to the population situation is the challenge of food production. The a highest,priority has been given to rice, lndonesia's staple food. The introduction of new high-yield plant strains, multiple croppings better irrigation, chemical fertilizers and pesticides has resulted in a spectacular 50 per cent increase in rice production between 1974 and 1984, A government rice stockpiling and distribution network has also reduced the threat of famine. stabilized prices and provided credits and subsidies to farmers.

(Early oil exploration in Sumatra-where Indonesia's vital

oil revenue originated)

The problem has not yet been solved, however. Bad weather and insect infestations caused serious shortfalls in 1977. forcing Indonesia to import one third of the world's surplus rice. Since then, the introduction of a new pest-resistant rice strain and further intensification has raised average yields by 2l per cent, making Indonesia virtually self-sufficient in rice. Whether levels of production can keep pace with the rapidly increasing demand is the central question.The weather,of course,remains a key variable, though increase irrigation is reducing some of the uncertainty.

(As the world'sfifth largest OPEC producer,the nation's economy is heavily dependent on oil)

Other food and export crops have not fared so well. Production of vital crops such as rubber. copra, peanuts,oil palms, soybeans, cassava and maize has remained virtually stagnant over the past decade, and in some cases has actually declined. Sugar has been the notable exception. and is a possible model for future governmental intervention in other areas. Where as Indonesia spent US$700 million on sugar imports in 1981, increased cultivation and higher price incentives reduced the figure US$261 million in l982 and Indonesia now a nett exporter of sugar.

On the intensely cultivated island of Java it is estimated trait only a quarter of the population own land. And as the population expands, so agriculture absorbs a progressively smaller percentage of the total labor force. In 1960 the figure was over 75 per cent, while now only about 55 per cent of Javanese are engaged in food production. This has created a massive unemployment problem, in which millions of landless laborers have moved into the cities to seek work.

Some of these migrants have been absorbed into the budding manufacturing sector. Yet despite the priority afforded the development of an urban industrial base in the government's second five-year plan, repelita II, job opportunities in industry have not managed to keep pace with a labor force that is growing by 1.4 million a year. As a result, these young people lead a hand-to-mouth existence in the cities--driving pedicabs, peddling noodles and fried bananas, selling cigarettes, shining shoes and scavenging from garbage dumps. Their plight represents one of the major challenges facing Indonesia now.

Unfortunately. "the world economic recession and oil glut of the early l9S0s has created financial circumstances which have temporarily pushed all other problems to the rear. Indonesia has recently been forced to cut back oil production and to reduce prices significantly. The resulting drop in oil revenues exacerbated by the declining value of other key exports and reductions in foreign industrial investment, has led to a critical shortage of foreign exchange and a drop in the economic growth rate to only two per cent in 1982.

The guiding principles of the government's present economic strategy are export promotion and import substitution-selling more abroad and importing less. Oil refining is one area in which significant advances have been made towards the goal of self-sufficiency. Indonesia now boasts eight state-run refineries, the largest of which are in central Java and east Kalimantan, and refining capacity is now supply in gall of the domestic demand for kerosene and gasoline.

Significant savings have also been realized through domestic fertilizer production. Indonesia's first plant was opened at Palembang, South Sumatra, in 1964 with a capacity of I00,000 tons per year. Fed by abundant supplies of local natural gas, the state-owned plant has over the years developed into the world's largest urea-producing complex,now turning out more than 1.6 million tons a year.

In the realm of exports, lndonesia's most promising source of revenue is natural gas. Massive reserves totaling over 7l trillion cubic meters were discovered in east Kalimantan and in Aceh, northern Sumatra. In 197l, Since then, liquid natural gas (LNG) plants have been set into operation at both sites, and Indonesia now ranks as the world's number one exporter of LNG, with 1982 revenues of over US$2.6 billion.

Yet another industrial priority has been cement production. In the past decade the number of plants has more than trebled, and production has risen twelve fold.

Indonesia's other manufacturing industries are more embryonic. Almost 90 per cent of those employed in this sector work in small-scale cottage industries, producing basic items such as salt, coconut oil and furniture.Larger factories more dependent upon imported machinery and capital have had some success in supplying consumer goods for the local market in recent years.In 1982, for example, Indonesia produced 847,000 television sets, assembled 210,000 cars and trucks and over half-a-million motor bikes.

(Indonesia is also the world's exporter of natural gas)

The government has pinned its future hope son labour-intensive,export-oriented manufacturing and they are predicting an industrial "take-off " for Indonesia during the latter half of the 1980s. It is hoped that this will provide jobs and prosperity for a population that is expected to reach 1 212 million by the year 2,000.

Early 16th Century Portuguese map of Southeast Asia with much ofthe Indonesian archipelago undrawn

Early 16th Century Portuguese map of Southeast Asia with much ofthe Indonesian archipelago undrawn Early Dutch painting depicts a Sumatran volcano

Early Dutch painting depicts a Sumatran volcano Mangrovesa long the Cihandeuleum River at Ujung Kulon

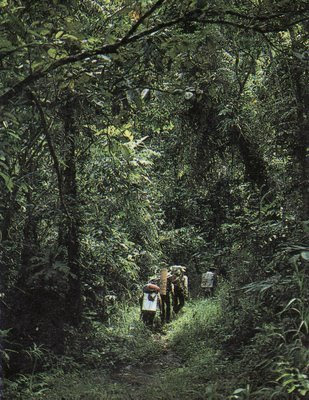

Mangrovesa long the Cihandeuleum River at Ujung Kulon Montane forest at Cibodas in West Java

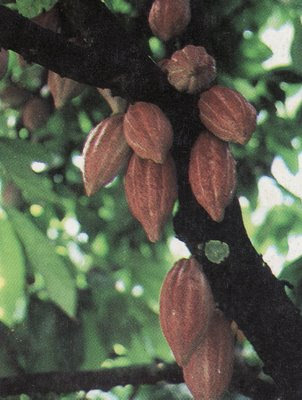

Montane forest at Cibodas in West Java Fruit of the cacao tree

Fruit of the cacao tree A wet-rice paddy in Sumba is "ploughed" by water buffal

A wet-rice paddy in Sumba is "ploughed" by water buffal Climbing a lontar palm for tuak

Climbing a lontar palm for tuak A tea plantation in the cool uplands of Java

A tea plantation in the cool uplands of Java (Jakarta's Gunung Sahara Street in the early fifties, a time of national reconstruction)

(Jakarta's Gunung Sahara Street in the early fifties, a time of national reconstruction) Sukarno (center) with his first cabinet, of which Hatta (right of Sukarno) was vice-president

Sukarno (center) with his first cabinet, of which Hatta (right of Sukarno) was vice-president ( Nehru (left) standing with Sukarno(right) During a state visit of 1957)

( Nehru (left) standing with Sukarno(right) During a state visit of 1957) (Right, Soekarno reads a statement to the press handing over power,

(Right, Soekarno reads a statement to the press handing over power, (In Jakarta, the monument commemorating

(In Jakarta, the monument commemorating (Early oil exploration in Sumatra-where Indonesia's vital

(Early oil exploration in Sumatra-where Indonesia's vital (As the world'sfifth largest OPEC producer,the nation's economy is heavily dependent on oil)

(As the world'sfifth largest OPEC producer,the nation's economy is heavily dependent on oil) (Indonesia is also the world's exporter of natural gas)

(Indonesia is also the world's exporter of natural gas)