History Of The Dutch in Indonesia

The saga of the Dutch in Indonesia began in 1596, when four small Dutch vessels led by the incompetent and arrogant Cornelis de Houtman anchored in the roads of Banten, then the largest pepper-port in the archipelago. Repeatedly blown off course and racked by disease and dissension, the de Houtman expedition had been a disaster from the start. In Banten, the sea-weary Dutch crew went on a drinking binge and had to be chased back to their ships by order of an angry prince, who then refused to do business with such unruly farang. Hopping from port-to-port down the north coast of Java, de Houtman wisely confined his sailors to their ships and managed to purchase some spices. But upon arriving in Bali, the entire crew jumped ship and it was some months before de Houtman could muster a quorum for the return voyage.

Arriving back in Holland in 1597 after ab absence of two years, with only three lightly laden ships and a third of their crew, the de Houtman voyage was nonetheless hailed as a success. So dear were spices in Europe at this time, that the sale of her meager cargoes sufficed to cover all expenses and even produced a modest profit for the investors!. This touched off a veritable fever of speculation in Dutch commercial circles, and in the following year fivce consortiums dispatched a total of 22 ships to Indies.

Arriving back in Holland in 1597 after ab absence of two years, with only three lightly laden ships and a third of their crew, the de Houtman voyage was nonetheless hailed as a success. So dear were spices in Europe at this time, that the sale of her meager cargoes sufficed to cover all expenses and even produced a modest profit for the investors!. This touched off a veritable fever of speculation in Dutch commercial circles, and in the following year fivce consortiums dispatched a total of 22 ships to Indies.

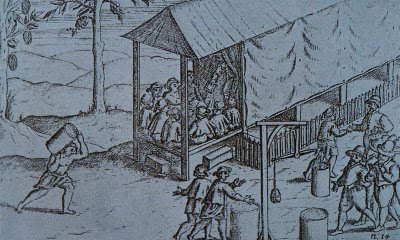

(Early Dutch expedition to Java)

(Early Dutch expedition to Java)The Dutch East India Company

(Van Lisnschoten - author of the first "guide book" to the Indies)

(Van Lisnschoten - author of the first "guide book" to the Indies)

The Netherlands was at this time rapidly becoming the commercial centter of Northern Europe. Since the 15th Century, ports of the two Dutch coastal provinces, Holland and Zeeland, had served as enter pots for goods shipped to Germany and the Baltic states. Many Dutch merchants grew wealthy on this carrying trade, and following the out-break of war with Spain in 1568, they began to expand their shipping fleets rapidly, so that by the 1590s they were trading directly with the Levant and Brazil.

Thus when a Dutchman published his itinerary to the East Indies in 1595-6, it occasioned the immediate dispatch of the de Houtman and later expeditions. Indeed, so keen was the interest in direct trade with the Indies, that all Dutch traders soon came to recognize the need for cooperation-to minimize competition and maximize profits. In 1602, therefore, they formed the United Dutch East India Company (known by its Dutch initials-VOC), one of the first joint-stock corporations in history. It was capitalized at more than 6 million guilders and empowered by the states-general to negotioate treaties, raise armies, build fortresses and wage war on behalf of the Netherlands in Asia.

Thus when a Dutchman published his itinerary to the East Indies in 1595-6, it occasioned the immediate dispatch of the de Houtman and later expeditions. Indeed, so keen was the interest in direct trade with the Indies, that all Dutch traders soon came to recognize the need for cooperation-to minimize competition and maximize profits. In 1602, therefore, they formed the United Dutch East India Company (known by its Dutch initials-VOC), one of the first joint-stock corporations in history. It was capitalized at more than 6 million guilders and empowered by the states-general to negotioate treaties, raise armies, build fortresses and wage war on behalf of the Netherlands in Asia.

(Van Lisnschoten - author of the first "guide book" to the Indies)

(Van Lisnschoten - author of the first "guide book" to the Indies)The VOC’s whole purpose and philosophy can be summed up in a single word-monopoly. Like the Portuguese before them, the Dutch dreamed of securing absolute control of the East Indies spice trade, which traditionally had passed through many Muslim and Mediterranean hands. The profits from such a trade were potentially enormous, in the order of several thousand per cent.

In its early years the VOC met with only limited success. Several trading posts were opened, and Ambon was taken from the Portuguese (in 1605), but Spanish and English, not to mention Muslim, competition kept spice prices high in Indonesia and low in Europe. Then in 1614, a young accountant by the name of Jan Pietieszoon Coen convinced the directors that only a more forceful policy would make the company profitable. Coen was given command of VOC operations, and promptly embarked on a series of military adventures that were to set the pattern for Dutch behavior in the region.

In its early years the VOC met with only limited success. Several trading posts were opened, and Ambon was taken from the Portuguese (in 1605), but Spanish and English, not to mention Muslim, competition kept spice prices high in Indonesia and low in Europe. Then in 1614, a young accountant by the name of Jan Pietieszoon Coen convinced the directors that only a more forceful policy would make the company profitable. Coen was given command of VOC operations, and promptly embarked on a series of military adventures that were to set the pattern for Dutch behavior in the region.

(Jan Pieterszoon Coen, architect of Dutch empire in the East)

(Jan Pieterszoon Coen, architect of Dutch empire in the East)The Founding of Batavia

Coen’s first step was to establish a permanent headquarters at Jayakarta on the north-western coast of Java, close to the pepper producing parts of Sumatra and the strategic Sunda Straits. In 1618, he sought and received permission from Prince Wijayakrama of Jayakarta to expand the existing Dutch post, and proceeded to throw up a stone barricade mounted with cannon. The prince protested that fortifications were not provided for in their agreement and Coen responded by bombarding the palace thereby reducing it to rubble. A seige of the fledgling Dutch fortress ensued, in which the powerful Bantenese and a recently arrived English fleet joined the Jayakartans. Coen was not so easily beaten, however (his motto:”Never Dispair!”), and escaped to Ambon leaving a handful of his men in defense of the fort and its valuable contents.

Five months later, Coen returned to discover his men still in possession of their post. Though outnumbered 30-to-1 they had rather unwittingly played one foe against another by acceding to any and all demands, but were never actually required to surrender their position due to the mutual suspicion and timidity of the three attacking parties. Coen set his adversaries to flight in a series of dramatic attacks, undertaken with a small force of 1,000 men that included several score of fearsome Japanese mercenaries. The town of Jayakarta was razed to the ground and construction of a new Dutch town begun, eventually to include canals, drawbridges, docks, warehouse, barracks, a central square, a city hall and a church-all protected by a high stone wall and a moat-a copy in short, of Amsterdam itself.

Coen’s first step was to establish a permanent headquarters at Jayakarta on the north-western coast of Java, close to the pepper producing parts of Sumatra and the strategic Sunda Straits. In 1618, he sought and received permission from Prince Wijayakrama of Jayakarta to expand the existing Dutch post, and proceeded to throw up a stone barricade mounted with cannon. The prince protested that fortifications were not provided for in their agreement and Coen responded by bombarding the palace thereby reducing it to rubble. A seige of the fledgling Dutch fortress ensued, in which the powerful Bantenese and a recently arrived English fleet joined the Jayakartans. Coen was not so easily beaten, however (his motto:”Never Dispair!”), and escaped to Ambon leaving a handful of his men in defense of the fort and its valuable contents.

Five months later, Coen returned to discover his men still in possession of their post. Though outnumbered 30-to-1 they had rather unwittingly played one foe against another by acceding to any and all demands, but were never actually required to surrender their position due to the mutual suspicion and timidity of the three attacking parties. Coen set his adversaries to flight in a series of dramatic attacks, undertaken with a small force of 1,000 men that included several score of fearsome Japanese mercenaries. The town of Jayakarta was razed to the ground and construction of a new Dutch town begun, eventually to include canals, drawbridges, docks, warehouse, barracks, a central square, a city hall and a church-all protected by a high stone wall and a moat-a copy in short, of Amsterdam itself.

(Natives bring nutmegs for sale to a Dutch trading post at Banda Neira)

(Natives bring nutmegs for sale to a Dutch trading post at Banda Neira)The only sour note in the proceedings was struck by the revelation that during the darkest days of the seige, many of the Dutch defenders had behaved them selves in a most unseemly manners-drinking, singing and fornicating for several nights in succession. Worst of all, they had broken open the company storehouse and divided the contents up amongst themselves. Coen, a strict disciplinarian, ordered the immediate execution of those involved, and memories of the infamous siege soon faded-save one. The defenders had dubbed their fortress “Batavia,” and the new name stuck.

Coen’s next step was to secure control of the five tiny nutmeg-and mace-producing Banda Islands. In 1621, he led an expeditionary force there, and withing a few weeks rounded up and killed most of the 15,000 inhabitants on the islands. Three of the islands were then transformed into spice plantations managed by Duth colonists and worked by slaves.

In the years that followed, the Dutch gradually tightened their grip on the spice trade. From their base at Ambon, they attempted to “negotiate” a monopoly in cloves with the rulers of Ternate and Tidore. But “leakages” continued to occur. Finally, in 1649, the Dutch began a series of yearly sweeps of the entire area, the infamous hongi (war-fleet) expeditions de islands other than Ambon and Seram, where the Dutch were firmly established. So successful were these expeditions, that half of the islanders starved for lack of trade, and the remaining half were reduced to abject poverty.

Still, the smuggling of cloves and clove trees continued. Traders obtained these other goods at the new Islamic port of Makassar, in southern Sulawesi. The Dutch repeatedly blockaded Makassar and imposed treaties theoretically barring the Makassarese from trading with other nations, but were unable for many years to enforce them. Finally, in 1669, following three years of bitter and bloody fighting, the Makassarese surrendered to superior Dutch and Buginese forces. The Dutch now placed their Bugis ally, Arung Palakka, in charge of Makassar. The bloodletting did not stop here, however, for Arung Palakka embarked on a reign of terror to extend his control over all of southern Sulawesi.

Coen’s next step was to secure control of the five tiny nutmeg-and mace-producing Banda Islands. In 1621, he led an expeditionary force there, and withing a few weeks rounded up and killed most of the 15,000 inhabitants on the islands. Three of the islands were then transformed into spice plantations managed by Duth colonists and worked by slaves.

In the years that followed, the Dutch gradually tightened their grip on the spice trade. From their base at Ambon, they attempted to “negotiate” a monopoly in cloves with the rulers of Ternate and Tidore. But “leakages” continued to occur. Finally, in 1649, the Dutch began a series of yearly sweeps of the entire area, the infamous hongi (war-fleet) expeditions de islands other than Ambon and Seram, where the Dutch were firmly established. So successful were these expeditions, that half of the islanders starved for lack of trade, and the remaining half were reduced to abject poverty.

Still, the smuggling of cloves and clove trees continued. Traders obtained these other goods at the new Islamic port of Makassar, in southern Sulawesi. The Dutch repeatedly blockaded Makassar and imposed treaties theoretically barring the Makassarese from trading with other nations, but were unable for many years to enforce them. Finally, in 1669, following three years of bitter and bloody fighting, the Makassarese surrendered to superior Dutch and Buginese forces. The Dutch now placed their Bugis ally, Arung Palakka, in charge of Makassar. The bloodletting did not stop here, however, for Arung Palakka embarked on a reign of terror to extend his control over all of southern Sulawesi.

(On the site of Jayakarta, the new town of Batavia had many of the features

(On the site of Jayakarta, the new town of Batavia had many of the featuresof Amsterdaam)

The Dutch in Java

By such nefarious means the Dutch had achieved effective control of the eastern archipelago and its lucrative spice trade by the end of the 17th Century. In the western half of the archipelago, however, they became increasingly embroiled in fruitless intrigues and wars, particularly on Java. This came about largely because the Dutch presence at Batavia disturbed a delicate balance of power on Java.

As early as 1628, Batavia came under Javanese attack. Sultan Agung (1613-46), third and greatest ruler of the Mataram kingdom, was then aggressively expanding his domain and had receltly concluded a successful five-year siege of Surabaya. He now controlled all of central and eastern Java, and next, he intended to take western Java by pushing the Dutch into the sea and then conquering Banten.

He nearly Succeed. A large Javanese expeditionary force momentarily breached Batavia’s defences, but was then driven back outside the walls in a last-ditch effort led by Governor-General Coen. The Javanese were not prepared for such resistance and withdrew for lack of provisions. A year later in 1629, Sultan Agung sent an even larger force, estimated at 10,000 men, provisioned with huge stockpiles of rice for what threatened to be a protracted siege. Coen, however, learned of the location of the rice stockpiles and captured of destroyed them before the Javanese even arrived. Poorly led, starving and sick, the Javanese troops died by the thousands outside the walls of Batavia. Never again did Mataram pose at threat to the city.

Relations between the Dutch and the Javanese improved during the despotic reign of Amangkurat I (1646-77), one reason being that they had common enemies-the pesisir trading kingdoms of the north Java coast.

It was ironic, then, that the Dutch conquest of Makassar later resulted, albeit in directly, in the demise of their “ally”.

The Makassar warsof 1666-69, and their aftermath, created a diaspora of Makassarese and Buginese refugees. Many of them fled to eastern Java, where they united under the leadership of a Madurese prince, Trunajaya. Aided and abetted by none other than the Mataram crown prince, Trunajaya succesfully stormed through Central Java and pludered the Mataram capital in 1676-7. Amangkurat I died fleeing the enemy forces.

Once in control of Java, Trunajaya renounced his alliance with the young Mataram prince and declared himself king. Having no one else to turn to, the crown prince pleaded for Dutch support, promising to reimburse all military expenses and to award the Dutch valuable trade concessions. The bait was swallowed, and a costly campaign was promptly mounted to capture Trunajaya. This ended, in 1680, with the restoration of the crown prince, now styling himself Amangkurat II, to the throne.

By such nefarious means the Dutch had achieved effective control of the eastern archipelago and its lucrative spice trade by the end of the 17th Century. In the western half of the archipelago, however, they became increasingly embroiled in fruitless intrigues and wars, particularly on Java. This came about largely because the Dutch presence at Batavia disturbed a delicate balance of power on Java.

As early as 1628, Batavia came under Javanese attack. Sultan Agung (1613-46), third and greatest ruler of the Mataram kingdom, was then aggressively expanding his domain and had receltly concluded a successful five-year siege of Surabaya. He now controlled all of central and eastern Java, and next, he intended to take western Java by pushing the Dutch into the sea and then conquering Banten.

He nearly Succeed. A large Javanese expeditionary force momentarily breached Batavia’s defences, but was then driven back outside the walls in a last-ditch effort led by Governor-General Coen. The Javanese were not prepared for such resistance and withdrew for lack of provisions. A year later in 1629, Sultan Agung sent an even larger force, estimated at 10,000 men, provisioned with huge stockpiles of rice for what threatened to be a protracted siege. Coen, however, learned of the location of the rice stockpiles and captured of destroyed them before the Javanese even arrived. Poorly led, starving and sick, the Javanese troops died by the thousands outside the walls of Batavia. Never again did Mataram pose at threat to the city.

Relations between the Dutch and the Javanese improved during the despotic reign of Amangkurat I (1646-77), one reason being that they had common enemies-the pesisir trading kingdoms of the north Java coast.

It was ironic, then, that the Dutch conquest of Makassar later resulted, albeit in directly, in the demise of their “ally”.

The Makassar warsof 1666-69, and their aftermath, created a diaspora of Makassarese and Buginese refugees. Many of them fled to eastern Java, where they united under the leadership of a Madurese prince, Trunajaya. Aided and abetted by none other than the Mataram crown prince, Trunajaya succesfully stormed through Central Java and pludered the Mataram capital in 1676-7. Amangkurat I died fleeing the enemy forces.

Once in control of Java, Trunajaya renounced his alliance with the young Mataram prince and declared himself king. Having no one else to turn to, the crown prince pleaded for Dutch support, promising to reimburse all military expenses and to award the Dutch valuable trade concessions. The bait was swallowed, and a costly campaign was promptly mounted to capture Trunajaya. This ended, in 1680, with the restoration of the crown prince, now styling himself Amangkurat II, to the throne.

(19th Century prints capture some of the adjuncts of colonialism)

But the new king was then in no position to fulfill his end of the bargain with the Dutch-his treasury had been looted and his kingdom was in ruin. All he had to offer was territory, and although he ceded much of western Java to the VOC, they still suffered a heavy financial loss.

On December 31, 1799, Dutch financiers received stunning news-the VOC was bankrupt!. During the 18th Century, the spice trade had become less profitable, while the military involvement in Java had grown increasingly costly-this at least is the broad outline of events leading to one of the largest commercial collapses in history.

It was a great war in Java (1740-55), however, which dealt the death blow to delicate Dutch finances. And once again, through a complex chain of events, it was the Dutch themselves who inadvertently precipitated the conflict. The details of the struggles are too convoluted to follow here, but it began in 1740 with the massacre of the Chinese residents of Batavia, and ended 15 years later, only after many bloody battles broken alliances and kaleidoscopic shifts of fortune had exhausted (or killed) almost everyone on the island. Indeed Java was never the same again, for by the 1755 Treaty of Giyanty, Mataram had been cleft in two, with rival rulers occupying neighboring capitals in Yogyakarta and Surakarta. Nor did the VOC ever recover from this drain on its resources, even though it emerged at this time as the pre-eminent power on Java.

On December 31, 1799, Dutch financiers received stunning news-the VOC was bankrupt!. During the 18th Century, the spice trade had become less profitable, while the military involvement in Java had grown increasingly costly-this at least is the broad outline of events leading to one of the largest commercial collapses in history.

It was a great war in Java (1740-55), however, which dealt the death blow to delicate Dutch finances. And once again, through a complex chain of events, it was the Dutch themselves who inadvertently precipitated the conflict. The details of the struggles are too convoluted to follow here, but it began in 1740 with the massacre of the Chinese residents of Batavia, and ended 15 years later, only after many bloody battles broken alliances and kaleidoscopic shifts of fortune had exhausted (or killed) almost everyone on the island. Indeed Java was never the same again, for by the 1755 Treaty of Giyanty, Mataram had been cleft in two, with rival rulers occupying neighboring capitals in Yogyakarta and Surakarta. Nor did the VOC ever recover from this drain on its resources, even though it emerged at this time as the pre-eminent power on Java.

Daendels and Raffles

It is one of the great ironies of colonial history that to fully exploit that to fully their colony, the Dutch had to first lose their shirts. The domination of Java-achieved at the expense of VOC bankruptcy-profited the Dutch handsomely in the 19th Century.

In the traumatic aftermatch of the VOC bankruptcy, there was a great indecision in Holland as to the course that should be steered in the Indies. In 1800, the Netherlands government assumed control of all former VOC possessions, now renamed Netherlands India, but for many years no one could figure out how to make them profitable. A number of factors, notably the Napoleonic Wars, compounded the confusion.

A new beginning of sorts was finally made under the iron rule of Governor-General Marshall Daendals (1808-11), a follower of Napoleon who wrought numerous administrative reforms, rebuilt Batavia, and constructed a post road the length of Java.

The English interregnum-a brief period of English rule under Thomas Stamford Raffles (1811-1816)-followed. Raffless was in many ways an extraordinary man: a brilliant scholar, naturalist, linguist, diplomat and strategist, “discover” of Borobudur and author of the monumental History of Java. In 1811, he planned and led the successful English invasion of Java, and was then placed in charge of its government at the tender age of 32. His active mind and free trade philosophy led him to promulgate reforms almost daily, but the result was bureaucratic anarchy. Essentially, Raffles wanted to replace the old mercantilism system (from which the colonial government derived its income through a monopoly on trade), by one which income was derived from taxes, and trade was unrestrained. This enormous tast was barely begun when the order, came from London, following Napoleon’s defeat at Waterloo in 1815, to restore the Indies to the Dutch. Raffles’ legacy lived one, however. Many of his land taxes were eventually levied by the Dutch, and they in fact made possible the horrible exploitation of Java in later years. And his invasion of Yogyakarta in 1812 led ultimately to the cataclysmic Java War of 1825-30.

It is one of the great ironies of colonial history that to fully exploit that to fully their colony, the Dutch had to first lose their shirts. The domination of Java-achieved at the expense of VOC bankruptcy-profited the Dutch handsomely in the 19th Century.

In the traumatic aftermatch of the VOC bankruptcy, there was a great indecision in Holland as to the course that should be steered in the Indies. In 1800, the Netherlands government assumed control of all former VOC possessions, now renamed Netherlands India, but for many years no one could figure out how to make them profitable. A number of factors, notably the Napoleonic Wars, compounded the confusion.

A new beginning of sorts was finally made under the iron rule of Governor-General Marshall Daendals (1808-11), a follower of Napoleon who wrought numerous administrative reforms, rebuilt Batavia, and constructed a post road the length of Java.

The English interregnum-a brief period of English rule under Thomas Stamford Raffles (1811-1816)-followed. Raffless was in many ways an extraordinary man: a brilliant scholar, naturalist, linguist, diplomat and strategist, “discover” of Borobudur and author of the monumental History of Java. In 1811, he planned and led the successful English invasion of Java, and was then placed in charge of its government at the tender age of 32. His active mind and free trade philosophy led him to promulgate reforms almost daily, but the result was bureaucratic anarchy. Essentially, Raffles wanted to replace the old mercantilism system (from which the colonial government derived its income through a monopoly on trade), by one which income was derived from taxes, and trade was unrestrained. This enormous tast was barely begun when the order, came from London, following Napoleon’s defeat at Waterloo in 1815, to restore the Indies to the Dutch. Raffles’ legacy lived one, however. Many of his land taxes were eventually levied by the Dutch, and they in fact made possible the horrible exploitation of Java in later years. And his invasion of Yogyakarta in 1812 led ultimately to the cataclysmic Java War of 1825-30.

(The Dutch Army poses after a victory over Acehnese forces)

(The Dutch Army poses after a victory over Acehnese forces)From Carnage to “Cultivation”

So numerous were the abuses leading to the Java War, and so great were the atrocities commited by the Dutch during it, that the Javanese leader, Pangeran Diponegoro (1785-1855), has been proclaimed a great hero even by Dutch historians. He was indeed a charismatic figure-crown prince, Muslim mystic and man of the people-who led a series of uprisings against the Dutch trick; lured to negotiate, Diponegoro was captured and exiled to Sulawesi. The cost of the conflict in human terms was staggering-200,000 Javanese and 8,000 Europeans lost their lives, many more from starvation and cholera than on the battle-field.

By this time, the Dutch were indeed in desperate economic straits. All efforts at reform had ended in disaster, to put it mildly, and the government debt had reached 30 million guilders!. New ideas were sought, and in 1829, Johannes van den Bosch submitted a proposal to the crown for what he called a culture Stengel or “Cultivation System” of fiscal administration in the colonies. His unoriginal notion was to levy a tax of 20 per cent (later raised to 33 per cent) on all land in Java, but to demand payment not in rice, but in labour or use of the land. This, he pointed out, would permit the Dutch to grow crops that they could sell in Europe.

Van den Bosch soon assumed control of Netherlands India, and in the estimation of many, his Cultivation System was an immediate, unqualified success. In the very first year, 1831, it produced a profit of 3 million guilders and within a decade, more than 22 million guilders were flowing annually into Dutch coffers, largely from the sale of coffee, but also from tea, sugar, indigo, quinine, copra, palm oil and rubber.

With the windfall profits received from the sale of Indonesian products during the rest of the 19th Century, almost a billion guilders in all, the Dutch not only retired their debt, but built new waterways, dikes, roads and a national railway system. Indeed, observes like Englishman J. B. Money whose book Java, or How To Manage A Colony (1861) was received in Holland with a great fanfare, concluded that the system provided a panacea for all colonial woes.

In reality of course, the pernicious effects of the Cultivation System were apparent from the beginning. While in theory the system called for peasants to surrender only a portion of their land and labour, in practice certain lands were worked exclusively for the Dutch by forced labour. The island of Java one earth, was thus transformed into a huge Dutch plantation. As noted by a succession of writers, beginning with Multatuli (nom de plume of a disillusioned Dutch colonial administrator, Douwes Dekker) and his celebrated novel Max Havelaar (1860), the system imposed unimaginable hardships and injustices upon the Javanese.

The long-range effects of the Cultivation System were equally insidious and are still being felt now. The opening up of new lands to cultivation and the ever-increasing Dutch demand for labour resulted in a population explotion on Java. From an estimated total of between 3 and 5 million in 1800 (a figure kept low, it is true, by frequent twas and famines), the population of Java grew to 26 million by 1900. Now the total has topped 110 million (on an island the size of New York State or England!), and the Malthusian time bomb is still ticking.

Another effect is what anthropologist Clifford Geertz has termed the “involution” of Javanese agriculture. Instead of encouraging the growth of an urban economy, as should have occurred under a free market system, Javanese agricultural development only encouraged more agriculture, due to Dutch intervention. This eventually created a twotier colonial economy in which the towns developed apart from the vast majority of rural peasants.

So numerous were the abuses leading to the Java War, and so great were the atrocities commited by the Dutch during it, that the Javanese leader, Pangeran Diponegoro (1785-1855), has been proclaimed a great hero even by Dutch historians. He was indeed a charismatic figure-crown prince, Muslim mystic and man of the people-who led a series of uprisings against the Dutch trick; lured to negotiate, Diponegoro was captured and exiled to Sulawesi. The cost of the conflict in human terms was staggering-200,000 Javanese and 8,000 Europeans lost their lives, many more from starvation and cholera than on the battle-field.

By this time, the Dutch were indeed in desperate economic straits. All efforts at reform had ended in disaster, to put it mildly, and the government debt had reached 30 million guilders!. New ideas were sought, and in 1829, Johannes van den Bosch submitted a proposal to the crown for what he called a culture Stengel or “Cultivation System” of fiscal administration in the colonies. His unoriginal notion was to levy a tax of 20 per cent (later raised to 33 per cent) on all land in Java, but to demand payment not in rice, but in labour or use of the land. This, he pointed out, would permit the Dutch to grow crops that they could sell in Europe.

Van den Bosch soon assumed control of Netherlands India, and in the estimation of many, his Cultivation System was an immediate, unqualified success. In the very first year, 1831, it produced a profit of 3 million guilders and within a decade, more than 22 million guilders were flowing annually into Dutch coffers, largely from the sale of coffee, but also from tea, sugar, indigo, quinine, copra, palm oil and rubber.

With the windfall profits received from the sale of Indonesian products during the rest of the 19th Century, almost a billion guilders in all, the Dutch not only retired their debt, but built new waterways, dikes, roads and a national railway system. Indeed, observes like Englishman J. B. Money whose book Java, or How To Manage A Colony (1861) was received in Holland with a great fanfare, concluded that the system provided a panacea for all colonial woes.

In reality of course, the pernicious effects of the Cultivation System were apparent from the beginning. While in theory the system called for peasants to surrender only a portion of their land and labour, in practice certain lands were worked exclusively for the Dutch by forced labour. The island of Java one earth, was thus transformed into a huge Dutch plantation. As noted by a succession of writers, beginning with Multatuli (nom de plume of a disillusioned Dutch colonial administrator, Douwes Dekker) and his celebrated novel Max Havelaar (1860), the system imposed unimaginable hardships and injustices upon the Javanese.

The long-range effects of the Cultivation System were equally insidious and are still being felt now. The opening up of new lands to cultivation and the ever-increasing Dutch demand for labour resulted in a population explotion on Java. From an estimated total of between 3 and 5 million in 1800 (a figure kept low, it is true, by frequent twas and famines), the population of Java grew to 26 million by 1900. Now the total has topped 110 million (on an island the size of New York State or England!), and the Malthusian time bomb is still ticking.

Another effect is what anthropologist Clifford Geertz has termed the “involution” of Javanese agriculture. Instead of encouraging the growth of an urban economy, as should have occurred under a free market system, Javanese agricultural development only encouraged more agriculture, due to Dutch intervention. This eventually created a twotier colonial economy in which the towns developed apart from the vast majority of rural peasants.

(Susuhunan Pakubuwono X of Surakarta poses with a Dutch administrator.

(Susuhunan Pakubuwono X of Surakarta poses with a Dutch administrator.Relations between the Dutch and natives frequently led to tragic conflicts however)

Rhetoric and Conquest

Though a great deal of acrimonious debate took place in Holland after 1860, and a few significant reforms were gradually insituted under the Liberal Policy of 1870, there was more rhetoric in the colonies that progress. True, peasants were paid wages for their labour and given legal titles wages to their land, but wages were miniscule, taxes were high, and the land belonged to a few. Privately managed plantations largely replaced government ones after 1870, but in fact some government coffee plantations continued to employ forced labour well into the 20th Century.

Outside of Java, military campaigns were undertaken, throughout the 19th Century, to extend Dutch control over areas still ruled by native kings. The most bitter battles were fought against the powerful Islamic kingdom of Aceh, during a war which began in 1873 and lasted more than 30 years. Both sides sustained horrendous losses. In the earlier “Padri War” between the Dutch and Minangkabau of west-central Sumatra (1821-38), the fighting was almost as bloody, as here too, the Dutch were pitted against Indonesian inspired by Islam. In the east, Flores and Sulawesi were repeatedly raided and finally subdued and occupied by about 1905-6. And the success of a renegade Englishman, James Brooke, in establishing a private empire in northwestern Borneo the 1840s caused the Dutch to pay more attention to the southern and eastern coast of that island thereafter. But the most shocking incidents occurred on Lombok and Bali, where on three occasions (1894, 1906 and 1908), Balinese rulers and their courtiers stormed headlong into Dutch gunfire armed only with ceremonial weapons-after ritualistically purifying themselves for a puputan (royal suicide) and avoiding the humiliation of defeat. In some ways, these tragic puputans symbolize tha abrupt changes wrought by the Dutch at this time, for the end of the first decade of this century they had achieved the unification of the entire Indonesian archipelago, at the expense of her indigenous kingdoms and rulers.

Though a great deal of acrimonious debate took place in Holland after 1860, and a few significant reforms were gradually insituted under the Liberal Policy of 1870, there was more rhetoric in the colonies that progress. True, peasants were paid wages for their labour and given legal titles wages to their land, but wages were miniscule, taxes were high, and the land belonged to a few. Privately managed plantations largely replaced government ones after 1870, but in fact some government coffee plantations continued to employ forced labour well into the 20th Century.

Outside of Java, military campaigns were undertaken, throughout the 19th Century, to extend Dutch control over areas still ruled by native kings. The most bitter battles were fought against the powerful Islamic kingdom of Aceh, during a war which began in 1873 and lasted more than 30 years. Both sides sustained horrendous losses. In the earlier “Padri War” between the Dutch and Minangkabau of west-central Sumatra (1821-38), the fighting was almost as bloody, as here too, the Dutch were pitted against Indonesian inspired by Islam. In the east, Flores and Sulawesi were repeatedly raided and finally subdued and occupied by about 1905-6. And the success of a renegade Englishman, James Brooke, in establishing a private empire in northwestern Borneo the 1840s caused the Dutch to pay more attention to the southern and eastern coast of that island thereafter. But the most shocking incidents occurred on Lombok and Bali, where on three occasions (1894, 1906 and 1908), Balinese rulers and their courtiers stormed headlong into Dutch gunfire armed only with ceremonial weapons-after ritualistically purifying themselves for a puputan (royal suicide) and avoiding the humiliation of defeat. In some ways, these tragic puputans symbolize tha abrupt changes wrought by the Dutch at this time, for the end of the first decade of this century they had achieved the unification of the entire Indonesian archipelago, at the expense of her indigenous kingdoms and rulers.

0 comments:

Post a Comment